Claude Sauvageau, director of testing and capital projects at PMG Technologies in Blainville, Quebec, Canada, recalls a monumental project on which he had to venture beyond his automotive roots.

I’ll never forget…

…working on the development of an FAA crash standard.

It was back in 1998 that I received an interesting request from a government client. I was a relatively young test engineer, having received my professional license in 1995, so I was always on the lookout for new and interesting projects that would test both me and my staff. The initial phone call had me hooked in less than 10 seconds: the chance to work on a project for the development of an FAA crash standard (the resulting standard is known as US Department of Transportation Federal Aviation Administration (FAA) Advisory Circular No 150/5345-45A).

The request, on paper, was simple: accelerate an airfoil to 150km/h (93mph) and impact the upper portion of an airport support tower to test its frangibility and energy absorption characteristics. Being primarily an automotive test and research center, we were no strangers to high-speed collisions and the application of precise data acquisition techniques, but this, I will admit, was something rather special.

Like with most things, what made this test special was not each individual component, but the sum of its parts. Installing a tower on our tracks was simple enough. Driving at 150km/h with an aircraft wing bolted to a truck, though riskier than a normal on-road test, was more than doable. Acquiring speed, strain gauge and load cell data and filming high-speed video of an impact was just another day at the office. But when all these things were put together, this test became rather symphonic in its complexity. So, like any good engineering team, we tackled each hurdle step by step.

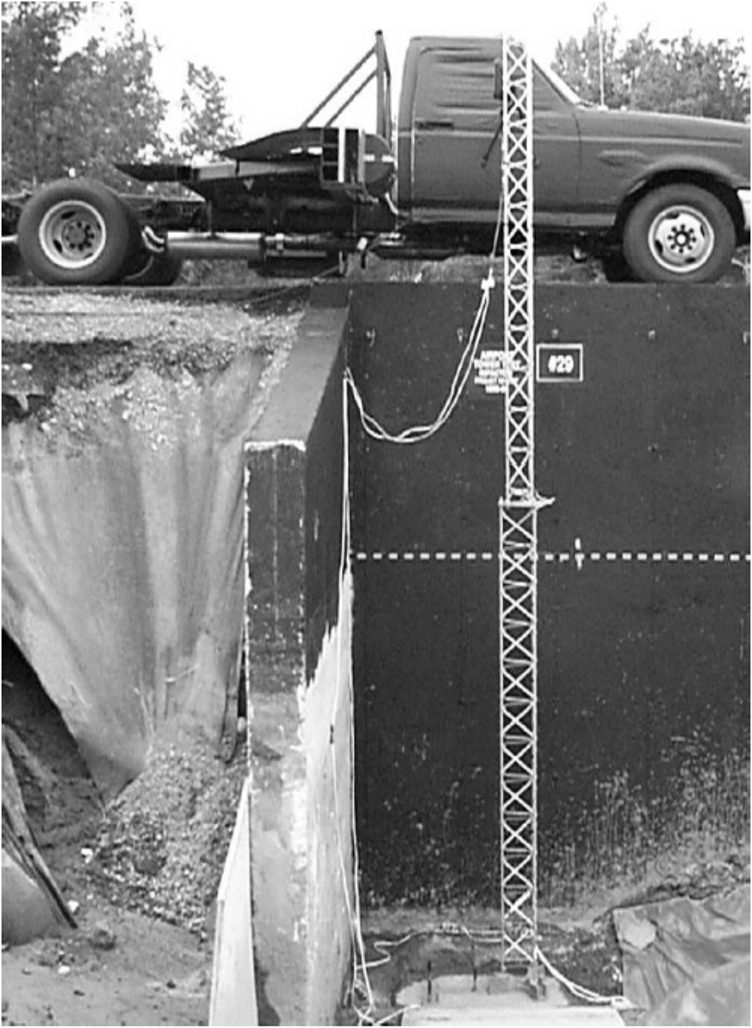

Installation of the tower ended up being a simple reference height problem, and if we couldn’t shift the tracks, we were to shift the tower. We ended up digging a trench around 6m deep, pouring a concrete slab at the bottom and anchoring the tower base to it. I’ll never forget standing next to one member of the maintenance crew, Michel Therrien, and looking down into the hole together, wondering if this would work, even though my calculations said it should.

Data acquisition and high-speed video were relatively routine as we performed track-based testing almost daily. Regardless, Richard Bélanger, the instrumentation expert on the project, was determined to make sure everything went perfectly.

This still left us with our airfoil problem: how were we supposed to impact the tower? I had an idea for a straightforward method for this and was curious to test it out. I ran the idea by a fellow test engineer, Alain Caron, one of our machinists, Jean-Claude Javet, and our client. They all seemed to believe it would work, but we’d need to find a driver who was borderline fearless. The idea was simple: we would reinforce the frame of our heavy-duty pickup truck and weld a steel frame supporting the airfoil to the bed. The airfoil would be positioned cantilever-style and protrude outward from the vehicle. Some quick math assuaged my fears that this would be dangerous. Given the properties of the tower, and the kinetic energy of the vehicle, the driver would barely feel an impact. Eventually, the test data from actual airfoils was used to develop the requirements for a simulated wing to be used instead, but for the first few tests our test vehicle was essentially a Ford F-350 with wings.

The linchpin in all this was the driver. Luckily, we had a bit of a daredevil on our test team. Michel Dufour was our go-to guy when it came to high-speed, high-precision tests. A former military driver, his first question when you asked him to drive something would be, “How fast?”. I distinctly remember his reaction when I proposed the test to him: he looked away into the distance, lost in thought for a second, scratched his chin, blinked a few times, and said, “Sounds fun, shame we couldn’t do it with a real plane.”

A few weeks later, testing day finally arrived. Everything was set up and going according to plan. The clients were in attendance and itching to see the tests and subsequent results. I was feeling the well-developed paranoia that all good test engineers feel, a confidence and trust in my team, our methods, and equipment, but a knowledge that I couldn’t relax for even a second as even one open channel, one improperly placed trigger or even one small error in our test procedure, or execution thereof, could invalidate the entire test. We checked, double-checked and triple-checked everything. Every bolt, weld, cable, sensor and tick mark in a checkbox. And finally, there was no more waiting and it was time to begin.

I positioned myself as close as possible to the tower without being in danger, annoyed I couldn’t be closer but knowing that I was safer at a distance. I grabbed my radio and checked to make sure everyone was ready. Their calm voices came through one by one, assuring me that their individual checks were done and their systems ready to go. Michel’s voice through the radio came last, telling me the truck was in gear and he was awaiting my signal. I took a breath and pressed the broadcast button: “Go!”

After what felt like an eternity, I saw the truck coming around the bend of our high-speed, oval track. Michel was still invisible to me given the distance, but I could picture his relaxed, confident grip on the wheel as I heard his co-pilot over the radio giving us updates on speed and closing distance. I looked around and saw the faces of my colleagues; they all had the same mix of excitement and stress on their faces that I know was mirrored on mine.

And just like that, impact! The airfoil smashed through the tower perfectly on target, the truck barely shaking as it drove by. Michel brought the vehicle to a relaxed stop as the tower was still reverberating with the shock of impact, its frame now bent like a metal flag in the wind.

I remember the grin on all of our faces as the test wound down, all the data and videos perfectly acquired and the clients congratulating us on a test well done. It’s moments like that that make you come into the office every morning, moments that fill you with pride in your team and satisfaction at a job well done.

But that moment only lasted for a few seconds as there was still work to be done. We had 26 other variants to test over the next few days and noon was fast approaching. Still with a small grin, I picked up the radio and told everyone to begin setting up for the next test.