The Artura is the next step in McLaren’s electrification efforts; a ground-up development regime taking hybrid technology to the core of the model range.

McLaren is no stranger to hybridization – electric assistance was fundamental to the P1’s hypercar performance in 2012 and the Speedtail’s 403km/h top speed run seven years later – but the Artura takes it into uncharted territory. Artura is the car maker’s first all-new model since the MP4-12C a decade ago, contending not only with the weight and complexity of a high-performance hybrid system, but bringing the cost close to the 570S it indirectly replaces.

“We’ve increased the number of people in our team with specialist hybrid engineering skills, both in simulation and physical testing,” explains the vehicle’s chief engineer, Geoff Grose. “Our continued strand

of hybrid research and development – from P1 through Speedtail and Artura – has helped with this. But Artura is built to reach far more of our customers, so the balance between investment and price is different.”

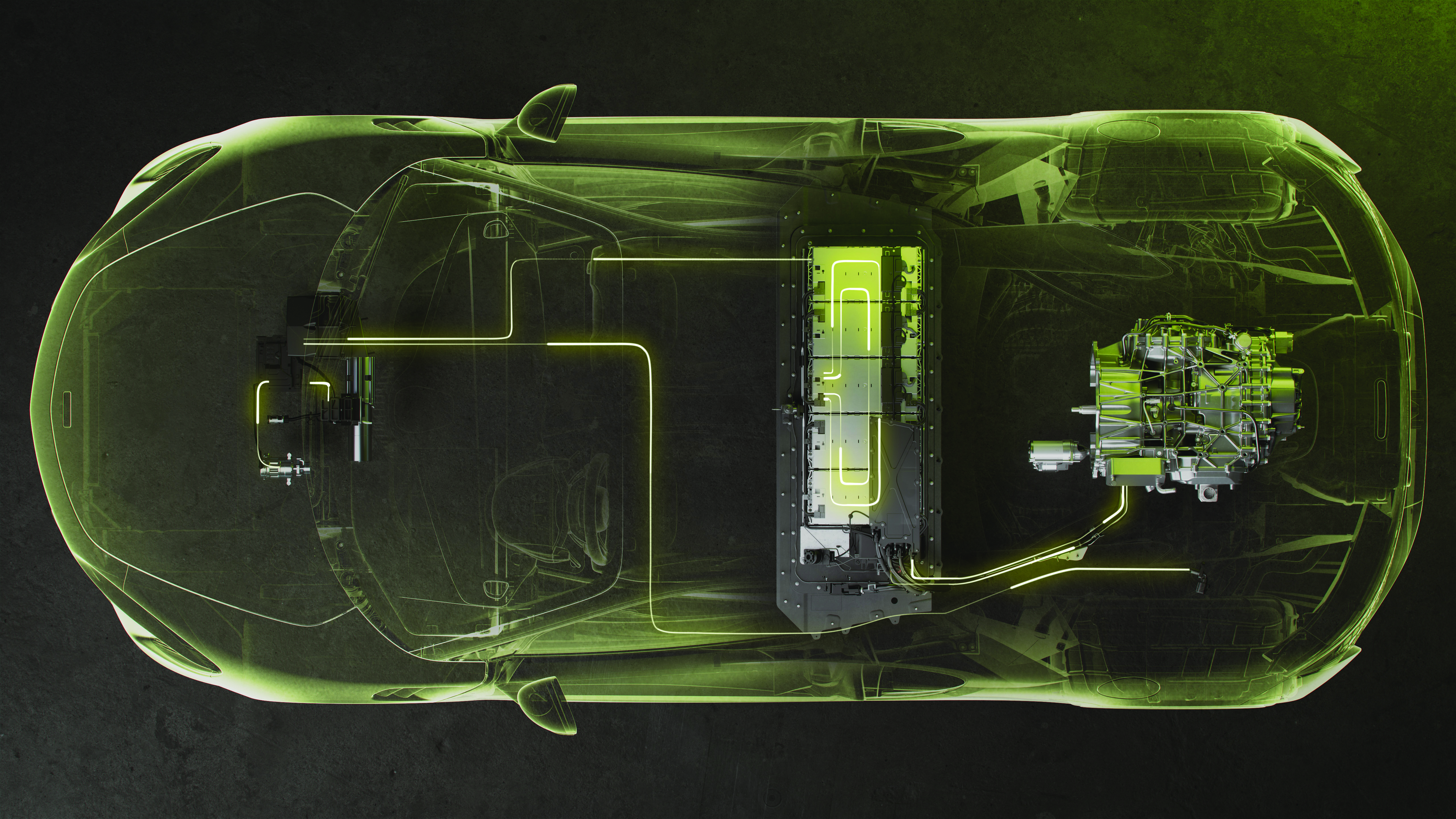

Development began with a spider chart around five years ago, setting out attributes for a new hybrid-only platform built around a mid-mounted electrified powertrain. The scalable McLaren Carbon Lightweight Architecture (MCLA) is the first product from the firm’s composites development and production facility near Sheffield, UK, and it’s designed for low weight, high stiffness and heavily automated production.

Less than 30% requires human intervention, compared with 80% for the MP4-12C.

The structure beneath Artura comprises a carbon-fiber monocoque with aluminum for the crash bars

and subframe, accommodating a powertrain which Grose says takes advantage of weight and size reductions for hybrid technology that were unavailable during previous vehicle projects.

Its 7.4kWh lithium-ion battery sits within a structural housing, paired with a pancake-shaped axial flux electric motor between the twin-turbocharged, wide-angle V6 petrol engine and 8-speed dual-clutch transmission. The new 12V electrical architecture is split into four domain controllers, located close to the systems they operate and connected via a high-speed Ethernet architecture, which cuts cable weight by 25%.

Balancing act

Such was the complexity of the hybrid system that it took shape ahead of the Artura’s silhouette. New 3D sketching technology, used for the first time on this project, enabled designers to quickly produce wireframes for CFD analysis and optimize chassis geometry with engineers.

Crash testing of MCLA prototypes began in 2019, by which point the hybrid system had been through in-house dyno testing and was being retrofitted to 570S-based mules, which Grose says required little or no camouflage.

“We were able to integrate early V6 engines, electric motors and transmissions into heavily modified versions of the previous vehicle to run as early development mules. Even before new parts make it into

the development vehicle fleet there are many different component and system level tests, for example engines running on dynamometers, and there is a lot more of this level of testing with a new platform development,” he explains.

“We didn’t have that background when we started on the 12C, so it was good to be able to work on a car that we knew really well and it was a lot easier than creating bespoke powertrain mules.”

Technical challenges were compounded by the onset of Covid-19 travel restrictions during the final stages of development. This reduced the size of teams that could be sent out to McLaren’s test facility at Idiada, Spain, requiring engineers to work alone where possible. As a result, a greater than normal share of the validation was carried out at sites in the UK, incorporating extensive durability testing based on data from McLaren’s existing road and race cars.

Nardò proved vital to that process. Alongside chassis tuning, a benchmark of the Artura’s hybrid system was its ability to provide full performance consistently during a 10-lap session at the Italian circuit. With no regenerative braking, engineers developed a charging strategy to quickly refill the battery using ‘spare’ energy from the engine and deploy it under load – torque infill from the motor provides the fastest throttle response yet. This also required three cooling circuits; the battery sharing its refrigerant with the cabin, the electric components with the charge coolers, and high-temperature radiators for the engine, with ducts flowing air through the turbochargers within its ‘hot vee’.

“Our learning on hybrid technology integration into our new McLaren Carbon Lightweight Architecture will be important for our future vehicle programs,” concludes Grose. “As we have done over the last decade, we will continue to push ourselves to keep developing the capability of our vehicles, now with added focus on hybrid technology.”